David Robinson Photos

Mexican Street Photography (Proposal)

1981. Recuerdos. “We sell memories,” the union president explains as we drive through the crowded streets. I am on a tour of Mexico City to observe and talk to itinerant photographers, those indigenous entrepreneurs who photograph customers for a fee on the streets and in public places. Itinerant photography exists throughout Mexico - and in fact in almost every country outside the industrialized world - serving people who do not own their own cameras and otherwise have little or no access to photography.

These are the indigenous chroniclers of their cultures, and poor people rely on them to record the major events of family life; the births, weddings, festivals, holidays etc. This is photography of, by and for the common man.

Despite its common touch - or perhaps because of it - until recently itinerant photography has been largely ignored by the photographic and academic communities. In fact, we know much more about obscure nineteenth century photographers, many of whom have become the subjects of reviews, exhibitions, books and academic theses than we do about the living indigenous itinerant photographers who still practice their trade among the common folk around the globe.

Mexico City. Thanks to a well run union and clever marketing, itinerant photography is a thriving enterprise. Even in the midst of rapid social change, it retains strong associations with the family and with the Mexican custom of celebration. The union - officially the "Union de Fotografos de Cinco Minutos y Polaroid" - runs all the itinerant photography in Mexico City and has some 400 photographers as active members.

There is a long tradition of itinerant photography in Mexico City, dating back to 1915, and the union itself has been in existence for almost forty years. The first part of the union name refers to the old paper negative process. In this process, the negatives are developed in small trays built into the back of the old wooden box cameras, then re-photographed with a special close-up attachment hinged on the front of the camera. The photographs of the paper negatives, developed again in the back of the camera, produce the positive prints. Prints are washed in a bucket kept between the legs of the tripod. The entire process takes about five minutes.

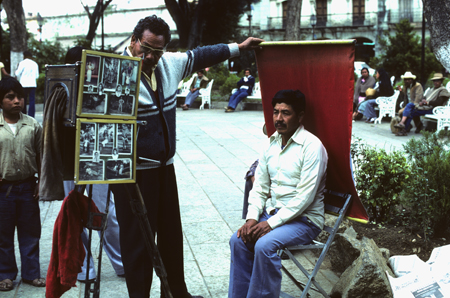

The paper negative process and the old wooden cameras perched on their creaky tripods are still commonly used in the smaller Mexican towns. In the past, photographers would travel with the rotating markets, and street photographers are still called “Los Ambulantes” in recognition of their history and to signify that they do not work inside in a fixed studio. Today in the small towns, Los Ambulantes can usually be found in the Zocolo, the main square. In Mexico City, almost all the photographers have switched to Polaroids, hence the updated part of the union's name. But even in Mexico City, the itinerant photographers keep the old cameras prominently displayed to advertise their presence and promote their service.

In the course of two visits, I visited three major sites, each several times, in order to sample the flavor of Mexican street photography and to learn firsthand about the union. First stop, the basilica at La Villa.

La Villa. Women with newly Christened babies, families fresh from the country, step forward, anxious but hesitant. The children are quieted, dresses straightened, posses assumed, faces set. Ready for the camera. Look good. Don’t blink. Deep breath. Appearoing with the Virgin or Pope, this is a solemn occasion, one to be recorded and preserved, an experience to cherish.

These are common people who have come to La Vila to worship and pay their respects to the Shrine of the Virgin of Guadalupe.. The Virgin is Mexico's patron saint, and La Villa is the country's religious epicenter, the center of popular folklore, devotion and inspiration. The new basilica holds 10,000 people, and every day hordes of pilgrims come to worship, often from afar, sometimes covering the last part of the pilgrimage inching forward on their knees. For many, an integral part of their experience is having their photograph taken, and there are 150 sidewalk photographers (working in shifts) there to serve them.

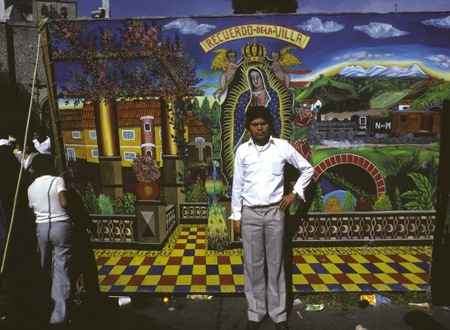

The grounds of La Villa are very large, and groups of photographers are stationed at various strategic points. At some locations, they use the basilica itself as their backdrop, while at others, they have made their own, all of which predominantly feature representations of the Virgin. Some are brightly painted free-standing constructions containing small statues, artificial flowers and photographs of the Pope. Like Victorian portrait studios, they have holes cut in them so that small babies can be held from behind by someone out of site while the babies have their picture taken. Other backdrops are large brilliantly colored naďf paintings done by one of the photographers, Jacinto Rojas. In addition to the blessed virgin, they depict idealized versions of typical Mexican scenes, thus linking the spirituality of La Villa to everyday life. The photographs place the customers in the center of this alliance and give them a souvenir of their experience to take home.

At La Villa, no one would think of acting out in front of the camera; the poses are serious as befits the nature of the occasion but also reflecting a lack of familiarity with being photographed. The solemnity with which the peasants face the camera is striking to anyone used to the Western snapshot culture with its emphasis on spontaneity and the unexpected. The candid shot which American culture values implies the hunter and the hunted, but this portraiture is truly a collaborative effort with everyone on the same wavelength. Photographers wait for their customers to present themselves as they wish to be photographed. There is no rushing and little direction by the photographer. The photographers know their customers, and in turn the people trust them.

Xochimilco. At the opposite end of Mexico City, Xochimilco offers a startling contrast to La Villa – it is the antithesis of La Villa. Xochimilco is the poor man’s Venice and promotes enjoyment and self-indulgence rather than devotion and denial. But here too the union has managed to make its photography an integral part of the scene, and as a result, business is thriving. After introductory tequilas with the union chiefs, I went out to have a look.

Everything is water-borne in Xochimilco. Hired boats (lanchitas) carrying Mexican families bent on having a good time are poled through canals clogged with vendors who paddle or pole alongside hawking food, drink, flowers or sarapes. Boats carrying mariachi bands blast out tunes for tips. Amidst all this, photographers also ply the waters selling their services. They place the old box cameras on tripods in their small boats to attract customers (but they use Polaroids). When taking a picture, the photographer ties his boat to the larger one and passes the necessary props back and forth. Here, photography is part of the fun, and people are more inclined to play in front of the camera. The photographer, balancing himself on his boat, framing the photograph, also directs his customers.

Straighten the huge sombrero. Adjust the sarape. Hold the flowers over her shoulder. Step forward a little so the colorful floral decoration of the lanchita can provide the proper backdrop. Wait until the boat is steady. There!. Congratulatory cheers for the customers resound from the surrounding boats.

By the time we return to land after an hour or so, like all the other visitors, we have been plied with beer, music, roses, all sorts of food – and of course most people take a photograph with them. The experience would not be complete without it. The photograph is a reminder of all this, a souvenir of celebration.

Christmas 1982. Mexicans celebrate Christmas with exuberance, so I arranged to return to Mexico City during the holidays, anxious to observe the street photographers in a third setting. I headed for the Alameda Park just after dark and found it transformed into a series of fantastic tableaus by the dozen or so photographers who have hired Santas, set up their sleighs surrounded by piles of colorfully wrapped presents and strung their backdrops and lights. An unbelievable setting, perhaps, but a highly photogenic one, which is of course the point, since these are sets specifically created to photograph the families jamming the Alameda at holiday time from late afternoon until well past midnight. The very presence of the photographers is what entices people to pass by on their evening stroll. There is competition here, for every photographer has his own crew and operation, and each has his own hawkers who shout come-ons. By the time I arrive, business is already brisk, and people are laughing and smiling.

Music boxes blare, bells chime and Santas work the crowd. Children climb into Santa’s arms or sit next to him in his sleigh to have their picture taken. After Christmas, Santas are replaced by the Three Kings, and the same procedure continues. People gather in a crush to watch, then, coaxed by the Santas or the Kings, parents step out from the crowd to pay their money and thrust forward their youngsters or babies to be photographed.

Howling infants struggle. Boys wearing droopy Zapata mustaches puff themselves up, and pretty girls with long curling eyelashes cuddle shyly in the sled next to their chosen Santa Claus. They are attended as needed by Jesus, one or all of the Three Kings and various snowmen and reindeer. It is hot, especially under the lights. The attentive parents wave frantically and shout instructions – Don’t cry! Sit up! Look here – here! Tears and laughter, flash. The photograph ejects, the children are rescued and replaced. The moment for them, this Christmas, is forever.

One of several photographers, Miguel Angel, (whom I dub the Michelangelo of itinerant photography) sits at a small wooden table under the spot lights for hours, hardly moving, waiting until each successive child is positioned. He rings a small bell hanging next to him frantically until the child looks his way. It takes a minute or minute and a half to get the child ready and take the picture. All the results are the same, all good, 50 packs of film (500 pictures) per day throughout the holiday season. As regular as clockwork. Its fun, and its profitable. Everyone goes away happy.

In all the time I spent with the street photographers, I never witnessed a photograph rejected by any customer. Nor did I see one that had to be re-shot. As a professional photographer, I find that astounding. I had many more problems with my Polaroid and Nikons than they did, but when my camera jammed, I didn’t have to worry; the street photographers were there to fix them in a jiffy. They offered to allow me to apprentice with them for a month or so in order to get the hang of it, and I was tempted to accept. I would have learned a lot.

I visited other sites as well, Chapaultapec Park and Piazza Garibaldi, and along the way I talked to the photographers and learned more about the union. Strictly speaking, it operates more like a guild than as a union. Among other things, it negotiates permits from municipal authorities, assigns photographers to specific locations and regulates the number at each site. The photographers rotate in shifts but do not rotate from site to site. The same group may work at the same location for years, and thus the photographers come to be closely associated with that place, both reflecting and contributing to its activity and local color.

Familial rights are recognized and reinforced by the union; when a photographer dies, his position is offered to his son. At Xochimilco, I met a young photographer who had gladly left his secure civil service position to take up his father’s camera after the father died. The union also runs a pension plan and a health clinic.

The Union. The union regulates all the commerce of sidewalk photography in Mexico City, buying film in bulk and selling it to members at five pesos more per pack. (This money, along with the twenty pesos per month union dues, goes to maintain the union activities). Prices are fixed by the union, and while they vary site to site, depending on the particular overhead expenses (hiring boats at Xochimilco, for example), at each site prices are kept uniform. Unlike most sidewalk or market retailing in Mexico, there is no haggling over price and no price competition. No photographer is allowed to overcharge or undersell. Among other things, this tends to upgrade the professional, image of the street photographers and helps create a sense of confidence that customers will get value for their money.

Photographs (Polaroid 108) in colorful plastic or cardboard frames cost between 70 and 100 pesos ($2.80 - $4.00), not at all cheap in a country with little disposable income. The popularity of itinerant photography in Mexico City reflects clever marketing by the union. But more than that, the photographers are part of the Mexican culture, indigenous and not exploitative. They have managed to interject photography into the deepest strains of Mexican religious and family life, and as long as Mexicans continue to value their memories, itinerant photographers will continue to prosper.

La Villa 1

La Villa 2

La Villa 3

La Villa 4

La Villa 5

La Villa 6

La Villa 7

La Villa 8

La Villa 9

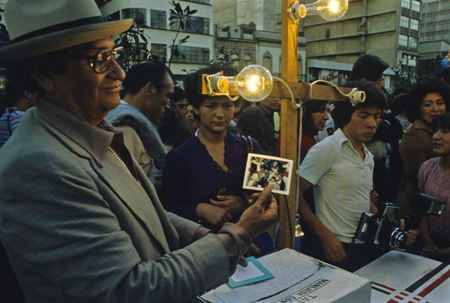

Xochimilco 1

Xochimilco 2

Xochimilco 3

Alameda 1

Alameda 2

Alameda 3

Alameda 4

Alameda 1

Alameda 7

Oaxaca 1

Oaxaca 2 Oaxaca 3

Oaxaca 4 Oaxaca 5

Oaxaca 6

Oaxaca 7